The Mediterranean diet, renowned for its abundance of healthy fats derived from olive oil and nuts, has long been associated with enhanced longevity and overall well-being when compared to diets high in fast food, meat, and dairy. However, the underlying cellular mechanisms that make this diet so beneficial have remained elusive.

In a groundbreaking study led by the Stanford School of Medicine, researchers have now discovered one of the first connections at the cellular level between monounsaturated fatty acids—specifically, the healthy fats present in the Mediterranean diet—and lifespan. This finding sheds light on the intricate relationship between diet, fats, and longevity.

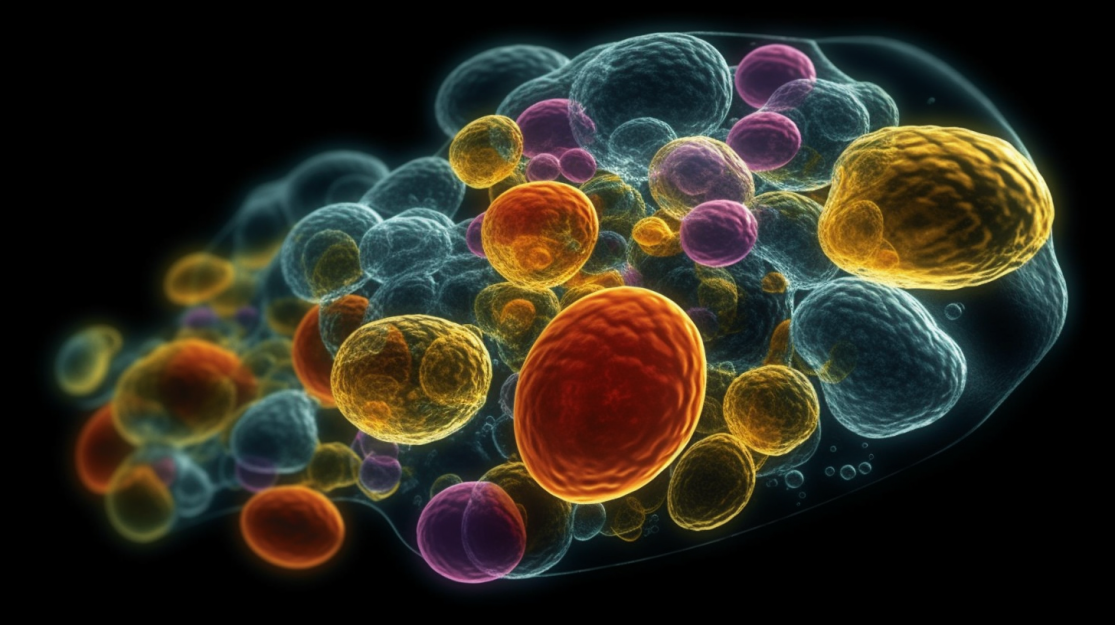

Contrary to the common notion that fats are generally detrimental to health, Professor Anne Brunet, Ph.D., a genetics expert, explains that certain types of fats, or lipids, can actually be advantageous. The study found that oleic acid, one of the fats prevalent in the Mediterranean diet, increases the number of crucial cellular structures known as organelles and safeguards cellular membranes from oxidative damage. This protective effect yields substantial benefits: Worms that were fed a diet rich in oleic acid lived approximately 35% longer than those consuming standard worm rations.

Interestingly, one particular organelle called lipid droplets proved to be a remarkable predictor of remaining lifespan, acting as a sort of crystal ball within the worms. Dr. Katharina Papsdorf, the lead author of the research, explains, “The number of lipid droplets in individual worms reveals the animal’s remaining lifespan. Those with a greater abundance of lipid droplets tend to live longer than those with fewer droplets.”

As the senior author of the study, Professor Brunet emphasizes the team’s longstanding interest in uncovering the influence of diet on lifespan. She comments, “It will be fascinating to determine whether we observe a similar association between lipid droplets and longevity in mammals and humans. These findings suggest that a fat-based strategy could potentially enhance human health and longevity.”

Unraveling the Language of Fats

Navigating the terminology associated with fats can be bewildering for those trying to distinguish between “good cholesterol” and “bad cholesterol” and seeking to cultivate a healthy balance. Generally, most monounsaturated fats found in plant-based foods such as avocados, olive oil, and nuts are considered relatively healthy. On the other hand, saturated fats and trans fats—solid at room temperature—pose an increased risk of heart disease and other health complications. Fats and oils consist of fatty acids, while lipids encompass fats, oils, fatty acids, and cholesterol.

In their longevity studies, Dr. Papsdorf and her colleagues employed a diminutive roundworm called C. elegans. These worms, measuring about 1 millimeter in length, naturally live for approximately 18 to 20 days. In their natural habitat, they inhabit soil and feed on bacteria found on decomposing plant matter. In the laboratory, they traverse lazily across the surface of specially prepared dishes teeming with bacteria. C. elegans reproduces rapidly, is cost-effective and easy to maintain, and its complete genome and neural networks have been meticulously mapped, rendering it an excellent model for studying aging and disease.

Dr. Papsdorf and her team compared the effects of feeding worms bacteria cultivated on laboratory dishes supplemented with oleic acid versus a structurally similar compound called elaidic acid. Elaidic acid, a monounsaturated trans fatty acid (trans fats being the undesirable variety!), is found in margarine and dairy products and is known to be detrimental to human health. Elaidic acid lacks a kink present in the molecular structure of oleic acid.

Professor Brunet elaborates on their observations, stating, “We observed an increase in the

numbers of lipid droplets in the worms’ intestinal cells when they were exposed to oleic acid, and this increase correlated with an extension of their lifespan. In contrast, exposure to elaidic acid did not lead to an increase in lipid droplet numbers and had no effect on longevity.

Lipid droplets serve as reservoirs for storing fats within cells and play a crucial role in cellular metabolism, regulating the utilization of fats as energy. The accumulation of these droplets proved to be essential for the positive effects of oleic acid. When genes responsible for producing droplet-making proteins were blocked, the worms’ lifespans returned to normal levels.

In addition to tracking lipid droplet numbers, the researchers also observed an increase in the number of peroxisomes in the intestinal tissue of worms exposed to oleic acid. Peroxisomes contain enzymes involved in metabolism and oxidation processes.

Both lipid droplets and peroxisomes are more abundant in younger animals and naturally decrease with age, suggesting a co-regulation between the two. Furthermore, their quantities can vary among individuals. Dr. Papsdorf discovered that among young worms fed a standard diet, those with higher numbers of lipid droplets lived slightly longer than their genetically identical counterparts with fewer droplets. This effect became more pronounced in older animals, as middle-aged worms with more lipid droplets lived an average of 33% longer than their peers with fewer droplets.

Professor Brunet notes an intriguing parallel with calorie restriction, which is also associated with increased longevity in animals and humans. Surprisingly, studies have revealed that among calorie-restricted mice, it is often the individuals with higher levels of fat who live the longest. This suggests that fat has a dual nature—some aspects can be highly detrimental, while others can be beneficial for longevity.

Protecting Cellular Membranes from Oxidation

Finally, the researchers demonstrated that oleic acid supplementation reduced a chemical reaction called lipid oxidation, which damages cellular membranes. In contrast, elaidic acid increased lipid oxidation. Professor Brunet highlights the significance of this finding, stating, “Membrane oxidation is extremely detrimental to an organism. It can lead to cell membrane leakage and failure, triggering a cascade of adverse biological effects.”

The researchers’ discoveries suggest that lipid droplets and peroxisomes are co-regulated through a biological pathway that responds to the presence of beneficial monounsaturated fatty acids. Protecting cellular membranes from oxidation may be a key factor in delaying the aging process.

However, Professor Brunet emphasizes that further research is necessary to determine how these findings apply to humans. While the presence of lipid droplets in mammalian tissue often indicates obesity and associated health issues, it is possible that droplets of specific sizes, shapes, or in certain tissues have varying health implications. Understanding these distinctions within the context of disease and longevity is crucial.

In conclusion, the study conducted by Stanford researchers offers valuable insights into the cellular connection between healthy fats, such as those found in the Mediterranean diet, and longevity. The findings highlight the positive effects of oleic acid on increasing the numbers of lipid droplets and peroxisomes, as well as protecting cellular membranes from oxidation. While the study was carried out in worms, it opens up exciting possibilities for further investigation in mammals and humans. By unraveling the intricate relationship between diet, fats, and cellular processes, we may uncover novel strategies to enhance human health and extend lifespan.

Cellular Fountain of Youth: Mediterranean Diet's Impact on Longevity Revealed